Behind heavy, blast-proof metal doors, buried dozens of feet underground and surrounded by reinforced concrete, you’ll find Texas’ command center for disaster response. Called “the bunker,” it is technically known as the State Emergency Operations Center (EOC) and is located in uptown Austin at the Texas Department of Public Safety’s main headquarters.

Although the facility is underground, it is essentially a self-contained office building. Amenities include a kitchen, showers, bunks, offices, meeting rooms and state-of-the-art communications equipment. Once you get through the narrow corridors, there’s a surprising amount of space, with desks and computers for representatives from almost every Texas state agency that plays a part in the state’s response to disasters like Hurricane Harvey.

When the Governor declares a disaster, state responders swing into action under the oversight of the Texas Division of Emergency Management. At that moment, state agencies are essentially working for and reporting to our Governor and his subordinates. Organized in Emergency Support Functions, the agencies assign trained personnel to the bunker, staff who know what resources the agencies can provide for the response. Some agencies handle environmental assessment, while others focus on transportation or utilities.

All agencies contribute their assets and knowledge of the impacted area and industries to protect the public and help with the recovery process. If a disaster grows in size and complexity, federal agencies like the U.S. Coast Guard and EPA will join the response structure and take the lead as needed. Information flows into the state EOC from local first responders, and services and assistance flow back from the state and federal government.

In 2005, I participated in the disaster response for Hurricane Rita. It made landfall at Sabine Pass, only weeks after Katrina had devastated New Orleans. Assigned to fly in a Black Hawk helicopter the day after the landfall, we were the first state responders to see the damage at ground zero from the air. We counted and evaluated structural damages (Does the building have a roof? Is it flooded?), sunken shipping, oil spills and containment, and reported the information back by satellite phone to our Austin EOC. Our report was then used to plan the next step of the disaster response.

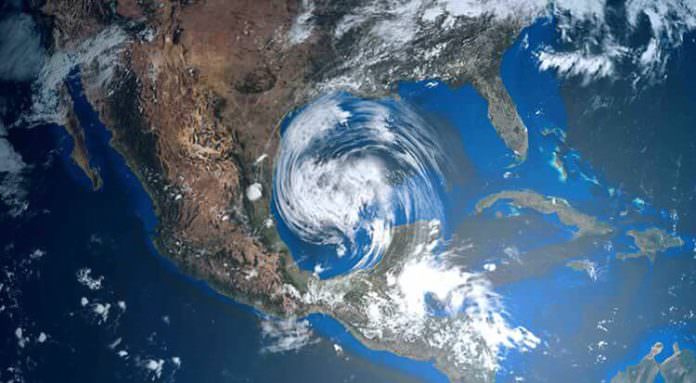

While hurricanes and the associated flooding are the bane of coastal living, Texas prepares for more than just storms. The state practices multiple drills that cover a host of scenarios, from nuclear facility incidents to power shortages. All follow a similar theme of escalating crisis. As events warrant, local responders contact the state for assistance or support, and the state responds. If needed, the state asks Washington, D.C., for assistance, and federal agencies respond.

To integrate this response into a cohesive whole, all entities — federal, state and local — follow the same principle of organization, the Incident Command System (ICS). The ICS is the primer for responses, and it stresses the Big Five of any response: finance, logistics, operations, planning. Together these fundamental building blocks spell C-FLOP, an acronym whose importance cannot be underestimated.

It is this combination of command, information, resources and field inspections that makes our disaster response flexible and effective. We practice FLOPS to ensure no response is a flop.

It is not easy work. We all know who is counting on us. And we all know the potential gravity of the situation. So as you watch the news and see trucks bringing supplies into disaster-torn communities, remember the planning and the people that make it all happen. They are highly dedicated men and women, and all Texans should be grateful for their service.

About the author: John Tintera, the Executive Vice President of the Texas Alliance of Energy Producers, is a regulatory expert and licensed geologist (Texas #325) with a thorough knowledge of virtually all facets of upstream oil and gas exploration, production and transportation, including conventional and unconventional reservoirs. As a former Executive Director and 22-year veteran of the Railroad Commission of Texas, considered the premier oilfield regulator in the nation, Tintera oversaw the entire regulatory process, from drilling permits to compliance inspections, oil spill response, pollution remediation and pipeline transportation.

Photo source: AdobeStock_169221358-1.jp