Things have gone from bad to worse. Following a year of lackluster oil pricing and a general decline in oil and gas E&P activity in Texas in 2019, oil markets are now reeling from the fallout of the coronavirus and its impact on energy demand growth in the U.S. and globally. What was poised to be another difficult year for the oil and gas industry in 2020 has now become something of a train wreck.

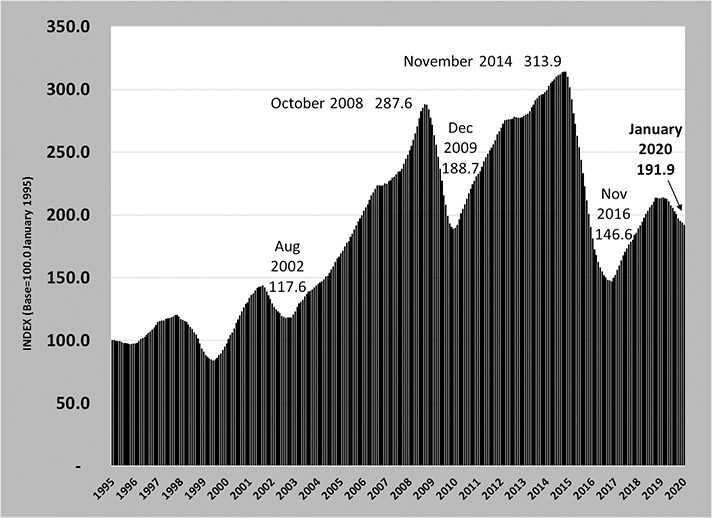

The Texas Petro Index measures growth rates and business cycles in the Texas upstream (exploration and production) oil and gas economy in Texas. The TPI is based on 100.0 in Jan. 1995. The most recent cycle of industry expansion began after the index troughed in Nov. 2016 following two years of sharp and debilitating contraction. That cycle of growth essentially came to an end in the fourth quarter 2018 with a sharp drop in oil prices. The index began to decline in earnest in March 2019 and has declined for 11 consecutive months March 2019 – Jan. 2020 (inclusive). That trend was set to continue this year, and the downward pressure has gained considerable momentum in the first quarter of 2020 thanks to COVID-19, otherwise known as the coronavirus.

The Texas Petro Index 1995-2020

The Texas Petro Index 1995-2020

At the heart of the matter is the simple fact that domestic and global petroleum markets are and have been amply supplied, a trend that was magnified with continued production increases in 2019. Even as the rig count, drilling permits, and industry employment declined throughout the year, U.S. crude oil production set yet another annual record at nearly 4.5 billion barrels, an increase of over 11% compared to the 2018 annual total. Over 41% of that production came from Texas, which also set another new annual record at 1.85 billion barrels for the year, an increase of 15% compared to the 2018 annual production.

U.S. Field Production of Crude Oil

U.S. Field Production of Crude Oil

It is U.S. (led by Texas) production growth that continues to push global crude oil production ever higher, and implied in the supply growth is the necessity to maintain a strong U.S. and global economy with accompanying energy demand growth sufficient to continue to absorb the ever-higher levels of production.

Texas Field Production of Crude Oil

The first hit to the global economy was the trade war, largely between the U.S. and China, which undoubtedly weakened the two largest energy-consuming economies on the globe. Trade wars, characterized by tariffs and protectionism, are virtually always economy-slowing events because the broad consumer economy takes a significant hit in the form of higher prices for a massive range of goods and services.

Even at that, crude oil prices averaged about $57 in 2019 for West Texas Intermediate, with posted prices for WTI averaging about $53.50 with very little change over the course of the year. The declines in the rig count and drilling permit numbers were slowing the rate of production growth nationally and in Texas, as markets were working to align supply with the evolving demand scenario.

In 2020, however, demand began to take new hits with the spread of the coronavirus and the growing alarm that has come with it. China — again as the second-largest energy consuming economy in the world — is ground zero for the origination and spread of the virus is an especially nasty punch to the face of crude oil markets. The drop in demand is evident in U.S. crude oil exports to China. While 2020 monthly data is not yet available, monthly crude oil exports began to decline in the second half of 2019 from a high of 8.75 million barrels in June to a paltry 536,000 barrels in December. Estimates of demand growth in China have been increasingly ratcheted downward and at present Chinese demand growth is expected to be non-existent in 2020 and will probably decline before all is said and done.

The same is true of the global demand picture. What was originally expected to be global demand growth of over 1.1 million barrels per day has now gone negative, with the dramatic decline almost exclusively the result of the coronavirus. The International Energy Agency (IEA) now expects global demand to actually decline in 2020 for the first time since the global recession of 2008 – 2009, anticipating a demand drop of 90,000 barrels per day, again compared to expectations only months ago of global demand growth of over 1.1 million barrels per day.

The shift in markets for the worse began to prompt discussions by Saudi Arabia, OPEC, and Russia to consider a coordinated pullback in production to help prop up crude oil prices. The idea, of course, is to adjust supply downward in response to the worsening demand scenario.

The expectations for just such an agreement were growing during the week of March 2, and these expectations seemed to be baked into crude oil markets going into the weekend of March 7-8. And that’s when things fell apart. Over that weekend, Saudi Arabia pushed for yet deeper production cuts by “OPEC+” (OPEC and other non-OPEC producers—Russia most notably).

Russia balked at those cuts and the weekend came and went without an agreement to cut production. The response in crude oil markets was swift and brutal; daily posted crude oil prices, which had already lost $17 a barrel since early January by Thursday, March 5 to $37.75 on Friday, March 6. The daily Plains All-American posted price on Monday, March 9 was $27.75, a drop of $15 a barrel in just two business days, and a decline of $32 a barrel since reaching $59.75 on Jan. 6, 2020, a decline of some 54% in two months. (This article was completed and submitted the morning of March 10.)

Not only did OPEC+ fail to agree to production cuts, Saudi Arabia in response to Russian reticence indicated it would actually increase production to a record 12.3 million barrels per day in the near term compared to current production of 9.7 million barrels per day, in what can only be described as a move to “flood the market” to achieve a geopolitical end. The scuttlebutt is that the Saudis are targeting Russia with the increased production, and that may well be the case as Saudi Arabia stands to lose the most in terms of market share absent Russia’s participation in the deal.

The ultimate result, however, is to put U.S. and Texas operators squarely in the line of fire in this standoff between Saudi Arabia and Russia. Both countries would clearly prefer that the U.S. provide the necessary production cuts to achieve a better market balance. But they are wary of waiting around for this to happen, having been burned by that strategy in 2016. And they know that any attempt by OPEC/non-OPEC to cut production to raise oil prices means that production cuts in the U.S. will not be as steep, if they even occur at all.

This is the essence of the great frustration that the United States provides to other crude oil-producing countries, Saudi Arabia and OPEC along with Russia in particular. Unlike those and most other producing countries in the world, there is no central mechanism for reducing crude oil production in the U.S. Production levels in the U.S. are simply the result of the decisions of thousands of individual private companies acting in their own best interests, rather than a collective best interest.

While most OPEC countries, certainly Saudi Arabia, as well as Russia, can produce crude oil much less expensively than can most U.S. shale producers, that is not actually the driving force behind their production decisions and their attempts to maintain prices at certain levels. Oil revenues provide the lion’s share of revenue to those governments and the massive social structures they support. They may talk a big game in the short term, and they may indeed decide to employ the market-flooding strategy for a while just to see if it (1) brings Russia back to the table, and/or (2) results in an observable significant production slowdown in the U.S. But the economic realities in those countries will force their hand at some point, and this will almost certainly not be a workable long-term strategy for that reason.

We should acknowledge, and do so with great pride, that oil and gas producers in the United States, with Texas leading the way, have utterly upended the global crude oil supply picture. The U.S. alone has added nearly 8 million barrels per day over the last 11 years with production growing from about 5 million bpd in 2008 to 12.8 million bpd at year-end 2019. Of that nearly 8 million bpd in U.S. production growth, 4.3 million bpd of that growth came from Texas, which has more than quadrupled its crude oil output from 1.1 million bpd in 2008 to 5.4 million bpd at year-end 2019.

U.S. production may peak and begin to decline at some point in the coming months in response to falling prices. It is instructive to note, however, that in response to an 80% price decline 2014—2016 and a 75%-80% decline in the rig count U.S. daily production declined by less than 12% – and it took 17 months for that to happen. Who knows, it may be different this time, but those who would profess to make a living predicting fast and sharp production declines in the U.S. would have gone broke multiple times over.

And while it is difficult to suggest, a slowdown in the U.S. (and Texas) E&P activity may indeed assist in aligning global supply and demand, and at the same time slow the incessant progression of unwanted growth in natural gas production.

What the current shock may do, however, is further endanger the U.S. and Texas independent producers, and small independents in particular. It is this group of operators with which the Texas Alliance of Energy Producers is most greatly concerned, and for whom we stand in the gap. For that reason, and for the health and prosperity of our global neighbors, here’s hoping coronavirus as a global phenomenon begins to evaporate sooner rather than later and Texas oil and gas producers can get on with the business of providing consumers with a steady, abundant, affordable supply of energy for the near term and the long term.

About the author: Karr Ingham is an Amarillo, Texas economist, and is the owner and President of InghamEcon, LLC, an economic analysis and research firm specializing in statewide, regional, and metro area economics, and oil & gas/energy economics.