In the field of economic development, the new watchword has become “sustainability” in all of its many manifestations. Even so, most mainstream economists — and their attendant economic models — fail to appreciate the bigger picture of what really makes an economy thrive for the long term. In the quest for a false sense of precision, the models that economists use have become ever more complicated and essentially incomprehensible to most policymakers.

Recent work in merging the abstract world of economics and the real world that the rest of us actually live in suggests that the most important environmental concern that countries are likely to face in the future will not be the availability of nonrenewable natural resources (witness the shale revolution) but rather the environmental sink — the ability of the earth to absorb waste and regenerate renewable resources (or ecosystem services). Closely related to this issue is determining what level of ecosystem services can be consumed at or below the regeneration rate of renewable natural capital. Important natural capital and ecosystem services, such as water, continue to be underpriced relative to their long-term value.

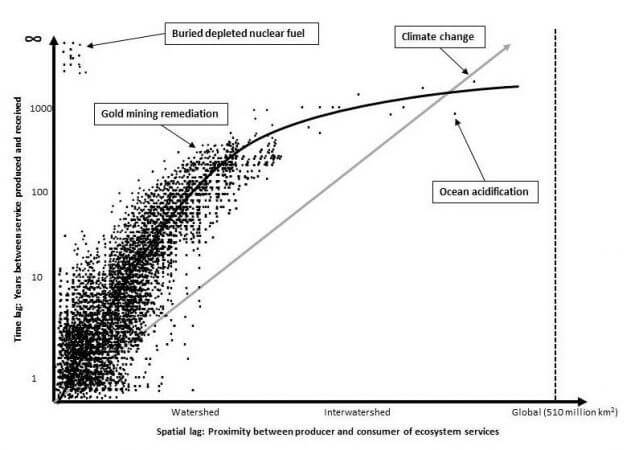

Part of the challenge from a policy standpoint is a lack of understanding of the full scope of interaction between the economy and the environment. Environmental impacts from industrial activity vary greatly in terms of space and time. Analysis can span several geographical scales: from local to regional to global. By the same token, some environmental impacts can be remediated relatively quickly, while others may require years or decades or even longer for regeneration of ecosystem services. Spatiotemporal scales of this sort are rarely if ever discussed systematically.

Yet to simply lump the environment into one big basket is a crude approach that does little to inform practical approaches for policymakers.

Hypothetical Distribution of Impacts to the Environmental Sink

In order to appreciate the path we are currently on, it’s instructive to look back at the broad sweep of history. Significant inventions and mass industrialization in the 20th century set in motion a large number of complicated interactions with the environment that researchers endeavor to understand. One such area of study involves appreciating the degree to which natural capital and ecosystem services influence not only economic but also social and political activity.

The prodigious rise in material prosperity over the 20th century, for example, tends to blind us to the degree to which the environment can still motivate politics and create societal turmoil.

The prodigious rise in material prosperity over the 20th century, for example, tends to blind us to the degree to which the environment can still motivate politics and create societal turmoil.

A recent example can be seen in the case of Syria. While there is a tendency to associate the civil war in Syria exclusively with the Assad regime and the Arab Spring, the reality is more complicated and tied to the environment more so than generally assumed. Prior to the 2011 uprising in Syria, the Fertile Crescent region experienced the worst drought on record. As a result, farmers and their families were displaced and forced to move to cities. In essence, what started as an environmental effect — the Syrian drought — soon escalated into civil war, whose proximate causes were a lack of food, loss of livelihood and poor governance. Evidence from investigation into the interaction between economics and the environment suggests that similar issues are likely to spark social upheaval in the future.

The linkages between long-term community, economic, social and environmental sustainability require the integration of economic development with ecosystem services. Too often the two still get treated as separate disciplines. Sustainability will be the rallying cry of the 21st century from a public policy framework, and the issue will continue to gain traction in the years ahead.

About the author: Thomas Tunstall, Ph.D., is the senior research director at The University of Texas at San Antonio Institute for Economic Development. He was the principal investigator for numerous economic and community development studies. He has published peer-reviewed articles on shale oil and gas, and has written op-ed articles on the topic for The Wall Street Journal. Dr. Tunstall holds a Ph.D. in political economy and an M.B.A. from The University of Texas at Dallas, as well as a B.B.A. from The University of Texas at Austin.