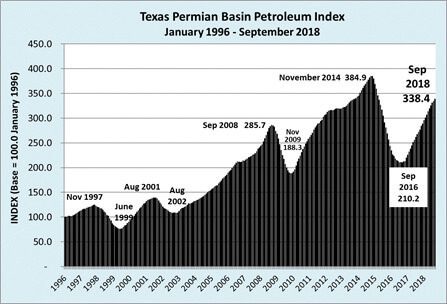

The Texas Alliance of Energy Producers has long been the owner and purveyor of the Texas Petro Index (TPI), an upstream (exploration and production) activity index that tracks growth rates and business cycles in the statewide Texas oil and gas exploration and production economy. The TPI, introduced by the Alliance in 2002, is based at 100.0 in January 1995 and has been calculated each month since then.

The original upstream activity index in Texas, however, was the Texas Permian Basin Petroleum Index, created in the late-1990s as a part of a general economic analysis package for the Midland-Odessa metro area, a partnership effort of the Midland Reporter-Telegram, the Midland Chamber of Commerce, and what was then First American Bank. In October 2018, the Texas Alliance of Energy Producers acquired the Texas Permian Basin Petroleum Index, and that association was announced at the Midland Petroleum Club Oct. 10.

The Texas Permian Basin Petroleum Index is based at 100.0 in January 1996 and has been calculated for each month now through September 2018. The components of the two indexes are nearly identical — prices paid to producers for crude oil and natural gas, the working rig count, the number of drilling permits issued, oil and gas well completions, the estimated volume and value of crude oil production, and the number of employees on upstream oil and gas company payrolls. (The employment total includes operating and producing companies, service companies and drilling companies.) The Texas Permian Basin Petroleum Index has an additional component: localized stock index. The basket of companies included in that index has changed over the years as companies have come and gone, but the present lineup includes Dawson Geophysical, Patterson-UTI, Concho Resources, Parsley Energy and Diamondback Energy.

The shape of the Texas Permian Basin Petroleum Index looks very similar over time to the TPI. The cyclical movements in the Permian regional oil and gas economy and the statewide upstream oil and gas economy largely mirror one another, which makes perfect sense, of course; the Permian numbers are a large part of the statewide numbers and price trends for crude oil and natural gas cause the same general movements and outcomes at the statewide and regional level.

The Texas Permian Basin Petroleum Index is thusly named because it includes only Texas numbers and does not cross over into New Mexico. The price data for crude oil is the monthly average posted West Texas Intermediate price and the gas price component of the index is the monthly average Waha Hub price. The rig count, drilling permits, well completions and production data are the sum totals for Texas Railroad Commission districts 7C, 8 and 8A. The employment data is the estimated oil and gas employment in the Midland-Odessa area (monthly payroll employment by sector is available only at the Metropolitan Statistical Area level).

As is the case with the TPI, the Texas Permian Basin Petroleum Index has now chronicled four complete cycles (expansion followed by contraction) with a fifth in the making. All of these cycles were significant in their own right, especially the 1998-99 contraction, the long expansion from 2002-2008 and the expansion 2010-2014 when Permian (and statewide) crude oil production exploded. The contraction beginning in the fourth quarter of 2014 was a brutal event in which crude oil prices declined by 80 percent, the regional rig count declined by 75 percent, drilling permits dropped by 70 percent, and some 10,500 industry jobs were lost in Midland and Odessa alone.

The index finally hit rock bottom in September 2016 and has now increased for two years — 24 straight months of expansion — through September 2018. Notably, however, for all the fantastic things that have occurred in the current recovery and expansion, particularly in terms of Permian crude oil production, the Texas Permian Basin Petroleum Index remains below its record peak achieved in the previous expansion in November 2014. Neither crude oil nor natural gas prices are as high now as they were then, the rig count remains below its late 2014 peak, and the number of drilling permits and well completions remain below 2014 levels as well.

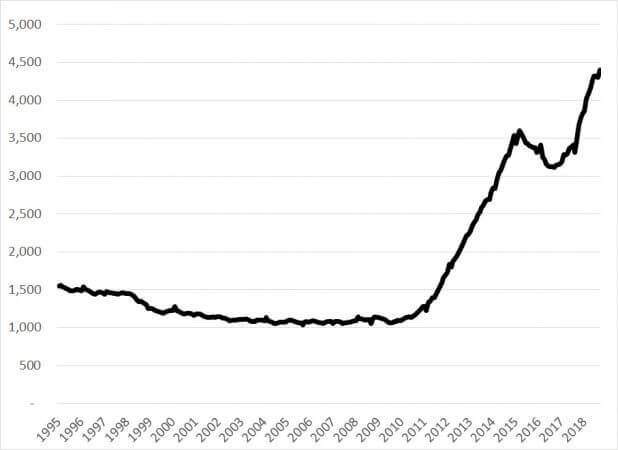

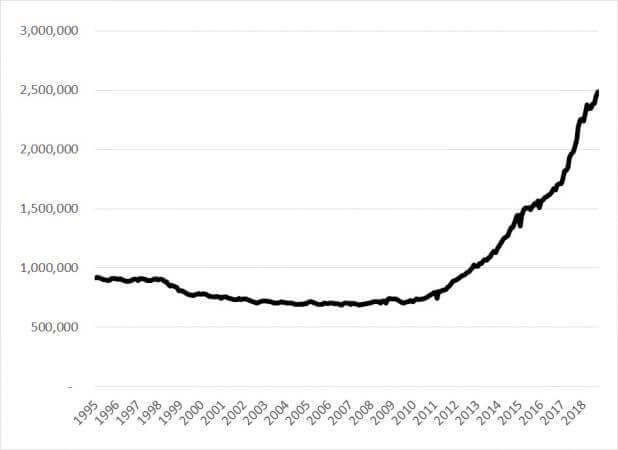

Crude oil production is the phenomenal story. And while that is the case for statewide Texas and the U.S., crude oil production did something quite remarkable — or rather didn’t do something — during the downturn.

Crude oil production statewide and in the Permian began to grow in earnest in 2010 on the heels of the recession-induced downturn of 2008-2009. Between 2010 and 2015 statewide daily crude oil production increased by over 2.5 million barrels per day, but then ultimately declined by nearly 14 percent between March 2015 and September 2016. Permian crude oil production, however, appeared to be utterly unfazed during the contraction and the only observable reaction was production growth at a somewhat lower rate — but it was growth nonetheless, and strong growth at that, even in the face of an 80 percent crude oil price decline and a 75 percent drop in the rig count.

The most high-profile phenomenon in the Permian in 2018 is clearly the takeaway capacity issue in which burgeoning crude oil and natural gas production have overwhelmed the pipeline capacity to move that production from the field to the marketplace. While relief is on the way in 2019, the effects are significant in 2018. Localized Permian crude oil prices are as much as $15 a barrel lower compared to posted WTI and Cushing prices, and Waha Hub natural gas prices are routinely $1 lower — sometimes more — compared to Henry Hub, the Houston Ship Channel and other pricing points.

A simple rough estimate based on current production at localized prices in 2018 suggests total unrealized production revenue of some $8 billion across the Texas Permian region, and that doesn’t include the high and rising volumes of flared natural gas. Natural gas production growth in the Permian (and statewide, for that matter) is largely accidental at this point, meaning it is simply associated gas production from crude oil wells. The natural gas takeaway capacity shortage limits the amount of that gas that can be marketed (though those volumes remain on the rise), hence the greater flaring volumes as permitted by the Railroad Commission.

The effects of the pipeline takeaway shortage may appear to be minimal ― the index continues its rise and production volumes continue to increase. Rig count growth has slowed (but not flattened, amazingly, though that still may happen), however a number of larger companies are shifting their focus to the Eagle Ford.

Texas Statewide Crude Oil Production (000’s BPD)

Texas Permian Basin Crude Oil Production (RRC Dist 7C, 8, 8A, 000’s BPD)

To learn more about TPI and the Texas Alliance of Energy Producers, visit texasalliance.org.

[…] to the Dallas Morning News, the Permian Basin, which produces almost 4 million barrels of oil a day, expanded so quickly that the electricity […]