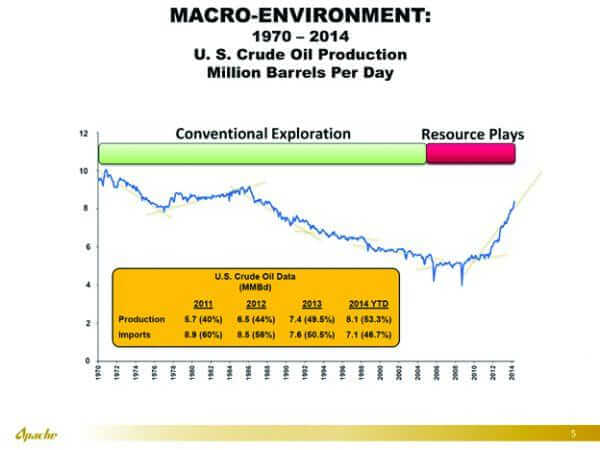

“My story starts in 1956 when I was one year old, and M. King Hubbard made a prediction about ‘peak oil.’ He said somewhere around 1970 U.S. production would peak at about 10 million barrels per day and then it would fall off over the next 25-30 years to about 4 million bpd, and the U.S. would be completely dependent on foreign oil.”

Steve Keenan is, to put it mildly, a high-energy individual. Apache Corporation’s Senior Vice President for Worldwide Exploration, he is a 40-year veteran of the oil and gas industry, a geoscientist who has seen it all and done most of it. As we start our interview last November, he is seated at his desk at the company’s offices on the western edge of San Antonio, trying to describe to this writer the series of events that led to the discovery of the massive Alpine High resource in the Delaware Basin of far West Texas. As we will soon see, it was a discovery that required a “cradle to grave” kind of approach, and true to form, Keenan was starting his explanation at the cradle.

“That’s important because people really believed what Hubbard was saying,” he continues. “And the amazing thing to me is that he was practically correct — oil did peak at 10 million bpd around 1970, and it did fall and we were disproportionally dependent on imports for a long time. But it didn’t fall in the logistic distribution curve that he predicted.” To emphasize this point, Keenan pulls up a line graph of the last 45 years of U.S. oil production onto his computer display. “If you’ll notice, there are changes in the slope of the curve, and it is those changes in slope that are the story of my career.

“Up until about 2005 the industry was involved in what we used to just call ‘exploration’ but which we now refer to as ‘conventional exploration,’ since we now have exploration in ‘unconventional’ or ‘resource’ plays,” he says, describing the different terms used to differentiate the sand and limestone formations from which almost all oil and gas was extracted during the industry’s first 150 years and the tight sands, coal and shale formations that have produced most of it in the U.S. during the course of the 21st century.

“All these changes in slope are important because what they represent are the introduction of new ideas, really creative and adaptive thinking, so that we could slow or arrest that decline. Or some kind of new engineering capability or new technology that didn’t exist previously. But mainly it was creative thinking.”

He points to a specific spot on the graph. “This is where I come in. I actually first got hired in 1978, after the Arab oil embargo and the discovery at Prudhoe Bay. Like a lot of people my age with my credentials (he has an MS degree, undergrad in geology with a master’s thesis topic pertaining to spectral analysis of seismic signals – most of his contemporary MS colleagues studying Geophysics were writing about the evaluation of gravity or magnetic data) I began my career working in frontier areas where all the big hopes were. The main suspects at that time were in Alaska and California.”

Indeed, the progression of Keenan’s career, which, before coming to Apache Corp. in June 2014 included stops at Cities Service Oil Company, SOHIO Petroleum, BP, Marathon and EOG Resources, reads basically as compendium of some of the largest major oil discoveries of the last 40 years.

As Keenan notes, the early years of his career, spent at Cities Service, were spent exploring for oil on the North Slope of Alaska and in California, where he worked on the huge Milne Point field 35 miles west of Prudhoe Bay, and also on the Point Arguello field in the Pacific Ocean waters offshore California, just north of Santa Barbara.

While working as Regional Project Manager and as Chief Geophysicist at a domestic independent oil company from 1985 through 1997, Keenan gained a wealth of international experience, exploring for oil faraway places like Norway, Oman, Spain, Argentina and Egypt. Keenan moved over to Marathon Oil in 1997, and spent the next five years working on assets in the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico and Angola.

Keenan next moved to become Division Exploration Manager of the South Texas operations for EOG Resources. There, he led the company’s highly-successful development of the Middle Wilcox tight sands assets in South Texas. Then, in 2008, his team made a major new discovery when it drilled, hydraulically fractured and completed the first successful horizontal well in the giant Eagle Ford Shale formation.

Wait, you’re thinking, didn’t Petrohawk drill that first successful Eagle Ford well? That is the common story, and, to be fair, Petrohawk was the first company to publicly announce a successful Eagle Ford completion, in October of 2008.

In 2008, EOG made a strategic decision to add more liquids to its portfolio of assets as the natural gas market in the U.S. began to become over-supplied. Keenan and his team were directed by then-EOG CEO Mark Papa at that time to go find more oil, even though it had been highly successful in drilling for the natural gas in the Wilcox formation for many years by then.

In the summer of that year, Keenan’s team which included current Apache employees Chester Pieprzica, Roberto Alaniz and Navneet Behl, drilled the Tully C. Gardner #94H, a 4,200’ lateral well in Webb County, Texas, which is in the wet gas window of the Eagle Ford Shale, and brought it online in August. So, why does the Petrohawk well continue to get the credit? Because EOG made the strategic decision to not make an announcement of its new discovery.

“At EOG, we decided that there was no value to us in telling people that,” Keenan says with a chuckle. “We convinced our management to move over to Karnes County (to the east) [to start up an expanded leasing program]. We then moved our rig over into Karnes County and drilled what was the first crude oil well in the Eagle Ford Shale.

“If you think about it, what business advantage would we [EOG] have to tell anybody about that first well?” Keenan says, noting that doing so would only serve to bring new competitors into the play area. “When we drilled that first well, we had about 15,000 acres under lease in the Eagle Ford,” he notes. In the coming months, EOG’s acreage position ultimately grew to more than 575,000 acres, and the company became one of the handful of biggest players in the Eagle Ford drilling boom that lasted through 2014, and is now seeing something of a revival today.

Shortly after Papa retired from EOG, Keenan made the decision to move along as well, this time coming into Apache Corporation, initially as its Managing Director of North American Unconventional Resources. From there he has quickly advanced to his current position as Senior Vice President for Worldwide Exploration.

The discovery of the Alpine High resource was no doubt a big factor in his rapid advancement within the organization.

A Resource with a Bad Reputation

The Alpine High has always been there — well, it’s been there for several hundred million years, anyway — just waiting for the right team of scientists to come along and find it. As things turned out, it took a team staffed by people with little or no prior experience in the Permian/Delaware Basin to make the discovery.

I first interviewed Keenan in August, 2016, shortly after Apache had made the initial announcement of the major new discovery, for a piece published on Forbes.com. During that interview, Keenan pointed to his team’s lack of previous experience in the region as a major factor in Apache’s ability to discover the Alpine High, meanwhile many companies that had come before had passed it by. As Keenan put it, his team’s lack of preconceived notions about the nature of the rock beneath the ground allowed it to “contravene the pre-existing dogma” about the play, and evaluate it through non-biased eyes.

Companies have explored for oil and gas in the general area for decades. Most previous exploration took place on the Northern and Eastern flanks of Apache’s current acreage position, although some early wells were drilled within it in the early 2000’s. At that time, companies were testing the Barnett/Woodford extension to see if it might be as productive as the Northeastern extent of the formation in the Dallas/Fort Worth area had been. Those efforts turned out to be only modestly successful, and preconceived notions about the reservoir quality and structural history of the area that now constitute the core of Apache’s acreage precluded any further serious testing in that portion of the play from taking place.

The drilling of hundreds of previous wells in the general area since the 1970s without much success had led producers in the area to develop a set of assumptions about the resource. The Alpine High had developed a reputation, it seems, that caused explorers with long experience in the region to shy away from it in favor of other prospective areas they believed were more likely to yield significant resource.

When Keenan and his crew put fresh eyes on the available seismic and other information, and gained management approval to begin drilling test wells, they soon developed an entirely different set of beliefs where the Alpine High was concerned. “In our case, having no preconceived notions, we were very interested in the source interval of the Woodford Barnett and the Pennsylvanian,” he told me in 2016. “That is not the play currently being made in the Delaware and Permian basins. We spent a lot of time and money looking at our own proprietary 3D seismic, drilled a couple of wells and systematically tested our concepts, including thermal maturity, minerology and history of movement. We concluded Alpine High was a play in which these major factors are favorable.”

Where the industry dogma dictated that the reservoir quality had very high clay content and would thus be difficult to effectively fracture, the Apache team concluded that the clay content in the key underground formations was actually quite low. Where the industry believed the structural history of the area was uplifted and highly complex, Keenan’s team concluded it was actually relatively stable. Where the dogma presumed that the underlying thermal maturity dictated that this would be, if anything, a dry gas play, the Apache team concluded it would in fact produce very rich wet gas and oil.

“There is a big difference between conventional and unconventional reservoirs, and that’s what keeps some companies from making discoveries,” Keenan continued in our November interview, “Because they don’t actually recognize the difference even though they know the language.

“The main thing to understand is that unconventional reservoirs are dynamic systems, as opposed to conventional reservoir systems, which are static. These extremely complex reservoirs require the right systems and understanding to accurately map them. That’s how we understood that the Alpine High was a major, major play.

“This is all about system permeability, because it has a macro, micro and nano scale. It’s not that hard — almost anyone can do it as long as they look at it the right way.” People had been looking at the Alpine High the wrong way for more than 40 years. Keenan’s team was the first to come along and change that.

Moving from Delineation to Development

When I ask Keenan to talk about the thickness — the vertical extent — of the Alpine High play, he responds with a gleam in his eye: “Well, I’m about to show you — it’s one of my favorite subjects.”

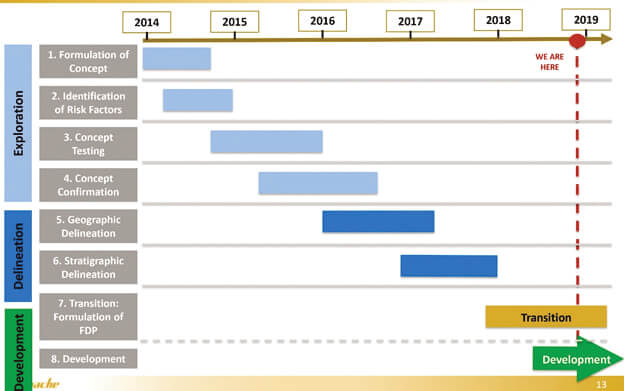

“What makes the Alpine High difficult is the dimensional complexity. We have to do not only geographic delineation, but also stratigraphic delineation,” he says, meaning that Apache must drill test wells in order to determine not just the boundaries of the surface extent of the play area, but also to measure the overall vertical extent and number of formations with commercial production potential. “Then comes development.”

“So, this is our timeline,” he says, pointing to another graph on the screen. “It took about two years (starting in 2014) to do geographic delineation, and more or less the same amount of time to do the stratigraphic delineation.

Right now, we are transitioning from delineation to the development phase.” Through its delineation process, Apache has determined that, in some parts of the play, the vertical extent of commercial formations stacked atop one another reaches a thickness of up to 5,500 feet.

Alpine High Development Timeline

In more than one of the test wells, Keenan says, the company was able to identify as many as 13 separate producing intervals. Pulling up another illustration, he points out, “Three producing zones in the Woodford, three in the Barnett, one in the Pennsylvanian, four in the Wolfcamp and two in the Bone Springs. That’s 13,” he notes with a grin.

Keenan points out that there had been some impatience from Wall Street to see the project move to the point of development, “but there’s a dimensional complexity here that can’t be overstated. Everybody says ‘so what’s taking so long?’ and I have to remind them that the Eagle Ford, which took three years to delineate, was just 90 to 220 feet thick, and it’s just one interval. Here we have 5,500 feet and 13 intervals.”

With so many producing intervals, the question of what order do you produce them in inevitably comes up. “You start deep and work your way up,” Keenan says. “You produce your deeper, source interval first, paying for all your necessary infrastructure as you’re doing that, and then you move up to the more shallow intervals. If you try to produce the shallow first, you lose the deep.” Makes sense.

It may have taken four years for Apache to get to the point of fully moving into the development phase, but the production numbers coming out of the Alpine High are already quite impressive. Alpine High production in the third quarter averaged 49,000 barrel of oil equivalent (BOE) per day, a 52 percent increase over the second quarter of 2018.

This obviously represents a tremendous rate of growth over a relatively short period of time. The company’s ability to control costs at the same time is equally impressive: “At the same time our lease operating expense has gone from $6.55 [a] barrel down to $3.00,” Keenan says.

“A lot of people say that if they have an oil play and you have a wet gas play, they have the superior asset. But we look at value optimization and capital efficiency quotient. What matters to us is the recycle ratio — what are our margins, and what was our finding cost? The main metric that justifies everything we do here is the quotient of margins and finding costs, and we have some of the lowest finding costs in the entire basin.”

As of our November interview, Apache had drilled right at 180 total wells in the Alpine High, and had eight active rigs in its drilling program. Thanks to its careful and systematic process of geographic and stratigraphic delineation and targeted initial drilling, Apache now believes it has a firm handle on the full extent of hydrocarbons in place within the Alpine High play.

Keenan points out that getting to this point was crucial for the next phase of the project, which is the design and building-out of the processing and transportation infrastructure that will be needed to break the raw gas stream down into its components and get the production to market. “The reason we had to have to have that high degree of confidence is the processing and transportation infrastructure for an area in which you start from zero is extremely capital intensive. In order for us to know how to size everything, and how to develop it, we have to first know what’s in place.”

He sits back in his chair and smiles. “So, what have I been doing on my summer vacation since the last time we talked?” he points to the screen, “I’ve been trying to figure all of this out.”

From the looks of things, he seems to have been pretty successful.

A Proactive Approach to Water and the Environment

“The biggest problem and operating expense for all the operators east of us is water – handling, transporting and disposing of it.” Keenan is pointing to another graph he has pulled up on his computer, this one comparing the water cut in an Alpine High well to several wells outside of the Alpine High delineated field.

I had just asked him to talk about the ways in which Apache is handling its water issues in this desert region of Texas, and he was quick to point out that while the Alpine High production is rich in liquids content, those liquids are mainly liquid hydrocarbons — the water content is actually very low compared to other plays in the basin. As Keenan puts it, “We have a hydrocarbon-wet system, not a water-wet system, and our initial water load just drops right off [after the well comes on-line].

“We have our own water transfer system within our 336,000 acres, so we are recycling almost all of the produced water anyway.” He points out that this lack of produced water is a key factor in the company’s ability to get its per-barrel lease operating expense to such a low level.

Still, water-related issues are always going to be a concern to the local public in any freshwater-poor region of the country, and activists immediately began ringing alarm bells in the area after Apache went public with the Alpine High discovery in the summer of 2016. Among other things, allegations were raised that Apache’s operations would deplete and/or contaminate the region’s underground freshwater aquifers, and that they would damage the huge swimming pool at nearby Balmorhea State Park, a local tourist attraction that is fed by naturally-occurring springs.

To mitigate these concerns and to ensure the safety of its own operations, Apache has from the outset of its operation worked closely with local officials, academics and regulators to ensure that any impacts from its operations to the region’s environment are minimized. Within a few weeks of announcing the discovery in 2016, Apache had entered into a partnership with The University of Texas at Arlington (UTA) to conduct a baseline groundwater study.

In addition to that, Castlen Kennedy, the company’s Vice President of Public Affairs, reminded me of other measures Apache has taken to avoid impacts to fresh groundwater aquifers in the area: “To meet our water needs, we are recycling our own produced water and are supplementing it with brackish water resources instead of freshwater. We have already built five water recycling systems in the Alpine High region and have developed brackish water sources from the non-potable Rustler Aquifer. In Alpine High, our goal is to source 100 percent of the water needed to supplement our recycled produced water program from non-potable water sources.”

She also pointed out that the company’s efforts to ensure minimal environmental impacts is not focused only on water, noting that Apache has also engaged with experts to conduct “extensive baseline research including air, water and soil studies and cultural, historical and surface impact assessments of the region.” She noted that Apache committed very early on not to drill wells “under Balmorhea State Park, the San Solomon Springs nor the town of Balmorhea,” although the company owns lease holdings in those areas.

Not only have the company’s operations done no damage to the Balmorhea Springs pool, when the pool suffered major structural damage due to ageing concrete and erosion in May 2018, Apache stepped up to the plate in a big way to help fund the repairs. The pool was built in the mid-1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps, and some of the concrete wall that supports the main diving board collapsed during annual cleaning operations that take place each May, prior to opening the pool for the summer. Working in partnership with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Foundation, the company committed the first $1 million in a joint effort to raise the $2 million needed fix the damage.

Actions like this, and many others the company has taken over the past two years, have helped calm the initial fears from some in the area, and denied local activists a major audience. The reality that the company’s operations have had no detrimental impact to the region’s water resources presents a case study for safe and responsible operations in water-sensitive areas of the country.

Meeting the Midstream Challenge

As most are now aware, getting new oil and gas production out of the Permian Basin has become a challenge in recent months as the existing system of pipelines has become fully subscribed. It should come as no surprise that this lack of pre-existing infrastructure was something Keenan and his team were fully aware of. As they went through the field delineation process, the team carefully evaluated and developed a detailed plan of action for how to address this issue.

“We have 150 miles of 30-inch and 24-inch trunkline built out, we have five refrigeration gas-processing plants, and we are in the process of building three cryogenic plants,” Keenan begins, “and we have firm commitments in place to move our oil, gas and NGLs out of the basin.”

As if to emphasize the point about planning and preparedness, just a few days prior to our November interview, Apache closed on a partnership deal with Kayne Anderson Acquisition Corp. to create Altus Midstream. Altus will own essentially all of Apache’s existent midstream infrastructure in the play, and will manage the build-out of the processing and gathering systems needed to ultimately eliminate the need for trucking and carry all the Alpine High production to mainline delivery points. In this deal, Apache retains ownership of 79 percent of Altus, which will also manage options to purchase equity interests in five top-tier, Permian Basin mainline pipeline projects, which will ultimately facilitate the movement the company’s production to ultimate markets.

With that, Keenan says it’s time to meet Navneet Behl, Apache’s dynamic Vice President of Unconventional Operations for North America. Behl and Keenan are on the same floor, but in offices in diametrically-opposite corners, so our walk transits the full length and breadth of the floor.

On this journey across the building, no visitor to the Apache offices could help but be struck by what can only be described as the phenomenal level of teamwork taking place among the staff. Everywhere you look you find people huddled up in conference rooms, break rooms and individual offices. It quickly becomes obvious that these are not people engaged in idle chat about their kids or last night’s TV shows — it is groups of co-workers from all disciplines collaborating in their efforts to find ways to solve problems and lower costs.

In talking with Keenan and Behl, the motivations behind all of this collaboration become readily apparent. Describing Behl as dynamic is, in fact, an understatement. This is a man who, in addition to working overtime each week in his job at Apache, flies out to MIT and back on weekends to participate in that university’s executive MBA program. It takes about 30 seconds of listening to him talk about his work and his team to realize that, just like Keenan, this is a guy who loves what he does, and that love for and dedication to the work is obviously contagious throughout the Apache offices.

Behl starts our discussion by demonstrating how he and others are able to monitor operations at Alpine High — well over 300 miles to the West — from the office in real time through the use of drone technology. The first footage he pulls up is an overview of the location where the three cryogenic processing plants are being constructed.

“This is one of the cryo plants here,” he says, pointing to the screen, where the drone is giving us a full shot of the construction area for the three plants, “and this is where all the fluid comes in, this is the stabilizer rack. So, you have one, two, three plants under construction, and we have room for three more.”

I asked next if the company had been impacted by the Trump administration’s tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum. “Not on the plant, but on some of the pipelines. After the tariffs came in, some of pipe costs went up 20 percent.” Just a part of doing business in the oil patch that most operators and midstream companies have had to endure in recent months.

He then went back to the drones. “Some of the drones are outfitted with the LDAR infrared camera equipment, so we can fly them over every one of our central tank batteries to check for leaks and we fix them proactively. In the past, many companies didn’t even know what was going on, but with this new technology we can do all of this remotely.”

Behl points to a partnership Apache recently entered into with a service provider that even allows the drones to automatically conduct the inspections on a predetermined schedule without human intervention. The data collected is then downloaded into the service provider’s software for analysis, which then notifies Apache personnel of any problems detected.

Behl next takes us over to another building that houses what Apache calls its “Fusion Center,” a facility from which teams of technicians monitor the volumes flowing from each well through the company’s gathering system and manages other elements of the Alpine High operation. On the way over he points out that he and Keenan opened the San Antonio office with just a handful of employees working out of two apartment units located in a housing/retail multi-use complex across the street from the current office tower, on which Apache now occupies two full floors. In the intervening two years the staff has expanded to more than 290, and will continue to grow in the coming years as the play develops.

In the Fusion Room facility, which actually consists of several different rooms, we watch as technicians monitor gas flows, well pressures, tank levels and many other elements of the oil field that in years past required human interaction in the field. At one point, we watch on a screen as a vacuum truck pulls up to a secured wellsite gate, and the technician has a short phone conversation with the driver 300 miles away to verify his credentials before clicking an onscreen button to open the gate and let him through.

After that, Behl notes one of his managers huddled in one of the corners with three other men, diagramming something on a whiteboard. He takes us over to the group and asks his man what they’re working on. As it turns out, the three other men are with one of Apache’s trucking contractors, and they are working on ways to improve safety and minimize downtime hours while working on Apache’s projects. This will not only cut costs for Apache, it will also benefit the trucking contractor by freeing up hours it can then dedicate to other customers.

In this office, the drive to control costs never stops.

Changing the Way the Oil Field Works

As our tour of the Fusion Center concludes, Behl summarizes all the uses of technology being employed by the Alpine High team in its continuous quest to streamline processes and lower costs, and concludes by saying, “We want to change the way the oil field works.”

They appear to be succeeding.

Back in Keenan’s office, he takes out a quote from a paper authored by Warren Buffett and Jamie Dimon: “The nation’s greatest achievements have always derived from long-term investments. In both national policy and business, effective long-term strategy drives economic growth and job creation.”

“What we have right now in our industry,” Keenan says, “is a predilection towards quarterly results and short-term profit, and a de-emphasis on effective long-term strategy. So, the industry has subordinated long-term strategy, as well as sustainability, in favor of short-term profits.”

He points to another quote, this one from former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. It says, “Don’t follow the crowd, let the crowd follow you.”

“That’s our view of exploration,” Keenan continues. “We don’t sit around like the Maytag repairman and wait for someone to call us and tell us what to do. We come up with our own ideas. Exploration is a search for the purpose of discovery, and discovery is defined as ‘the first detection of something new.’

“We have the vision as a company to be the premier exploration and production company, and our strategy for differentiation is to find high-impact, large-scale plays and — very importantly — deliver them at a low-entry cost. Our average lease bonus cost for the Alpine High is about $1,200 per acre,” far below what many competitors have been willing to pay in recent years in order to get their own piece of the Permian Basin.

When asked how many wells he believes the company will ultimately be able to drill on its 336,000 Alpine High acres through the full development of the field, Keenan, as is his habit, offers an unconventional answer: “We don’t know.” Oh.

But he goes on. “Our metric isn’t how many wells, it’s how do we maximize the net present value (NPV) on some kind of scaled basis.” He goes on to point out that the scale and metrics used to determine how many wells to drill per surface acre can vary from unit to unit and from section to section within the play. “What we’re trying to do is maximize recovery at the lowest cost. We want to figure out how to drill the fewest wells with the highest NPV. So, we can’t answer the question yet, because we’re in the transition from delineation to full development.

“Now, the question is recovery: How do we recover it to maximize value? We’ve got dimensional complexity that almost no other play has, that nobody could understand unless they came to this office.”

In the end, it was well worth the 275-mile drive from my home in Mansfield, just south of Fort Worth, to San Antonio, to sit down with Keenan and his team for this interview. Because he’s right: There was no way to really comprehend all the moving parts involved in making the Alpine High work without seeing it all in person.

It all brings to mind what Texas A&M graduates like to tell other people about their school’s unique culture: “From the outside looking in, you can’t understand it. And from the inside looking out, you can’t explain it.” To truly understand the complexity of the Alpine High and how Keenan and his team at Apache are changing how the oil field works in their management of it, you really do have to be there and see it firsthand.

About the author: David Blackmon is the Editor of SHALE Oil & Gas Business Magazine. He previously spent 37 years in the oil and natural gas industry in a variety of roles — the last 22 years engaging in public policy issues at the state and national levels. Contact David Blackmon at [email protected].